By Odmara Barreto Chang, MD, PhD, and Anika Sinha

Lack of diversity in the health sciences is a well-recognized problem with serious implications for the health and well-being of all communities. Resulting from hundreds of years of inequitable policies, laws, institutional and social structures, those from the African American, Hispanic / LatinX, Native American / Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander, and those whose ethnic make-up includes one or more races, are all under-represented in medicine [1]. A 1994 study published in the Journal of the Association for Academic Minority Physicians found that “…lack of awareness of opportunities in academic medical centers, lack of mentors, [and] a shortage of role models…” were also contributing factors [2].

In 2020, residents of American Indian/Alaskan Native (0.7%), Black/African American (6.0%), and Hispanic/LatinX (7.4%) backgrounds only made up <15% of all anesthesiology residents. Additionally, 42% of anesthesiology trainees reported that learning from women and a diverse faculty was somewhat or very important in their decision to pursue anesthesiology [3]. To support underrepresented minorities in medicine, upstream exposure to robust mentorship from diverse faculty is critical. Not only are the students inspired, but the patient population will ultimately reap the benefits. Growing evidence suggests that when healthcare teams reflect the diverse communities they serve, healthcare outcomes are optimized [4].

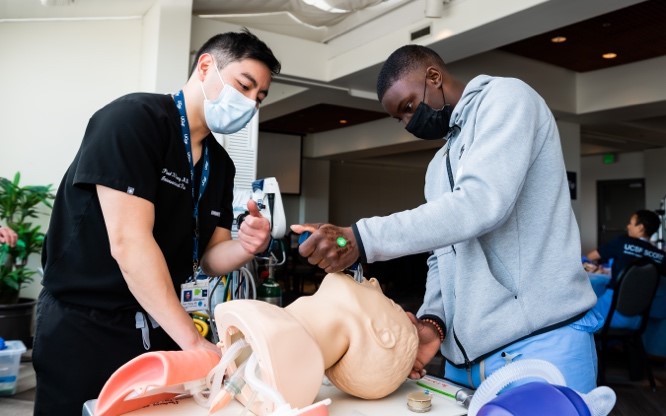

Experiential education as part of pipeline programs can help provide participants with a deeper understanding of health in their own communities as well as the wide range of career opportunities available to them in the health sciences [5]. An excellent example of this is the UCSF Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Care’s Students Capturing the OR Experience (SCORE) program. This opportunity enables San Francisco Unified School District high school students from underrepresented backgrounds to have first-hand exposure to multiple health sciences careers, mentors, and role models. Now in its sixth year, the 2023 SCORE events included Operating Room tours and hands-on stations for intubation, mechanical ventilation, organs, vital signs, ultrasound, and knot-tying. Students witnessed patient care in action and the dynamic and fast-paced perioperative environment [6].

Beyond UCSF, several other leading medical institutions have identified the need for diversity initiatives that target students early in their education. For example, the Stanford Medical Youth Science Program is a tuition-free immersive enrichment program focused on science and medicine that is open to low-income, first-generation high schoolers in California. Accepted students not only take anatomy and public health courses, but they get hands-on lab experience, participate in health-disparities research, shadow in hospitals, and receive academic-planning workshops to create a financial aid college plan [7]. A 2007 study on SMYSP’s impact showed that all 405 participants since the program’s inception in 1988 have graduated from high school, and 99% attended college. Most majored in biological and physical sciences (57.1%). Among four-year college graduates, 52% attended medical or graduate school [8]. It is evident that early robust mentorship and a strong alumni network from high school can pay dividends for a student’s academic career.

Another influential program is the FACES for the Future Coalition, which was founded in Oakland, California in 2000. This is a “comprehensive health careers pathway program that prepares socio-economically diverse high school students for careers that offer livable wages and upward mobility.” Ultimately, supporting these youth will help ensure we have highly qualified, multi-lingual, and multi-cultural health care professionals for future patients. Emphasizing the importance of continuous mentorship, FACES for the Future recruits students in their sophomore year and maintains their cohort until high school graduation. After securing a $2.5 million federal grant, the program was able to expand nationally to eight cities, including San Francisco, San Diego, Denver, Detroit, and Albuquerque. The target communities are diverse— such as San Diego’s City Heights neighborhood, where more than 40 languages are spoken and 35% of residents live in poverty. The program hones comprehensive skillsets for its students: health career experience via work-based internships and field trips; academic enhancement via college advising and career panels; and leadership development via culturally competent advocacy events. The results of such programs speak for themselves. With more than 1,800 students, FACES for the Future Coalition reported 100% of their participants graduate high school and more than 90% intend to pursue a health profession by their graduation [9].

Since 2016, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Committee on Professional Diversity has also made strides in community youth outreach tailored toward increasing awareness about anesthesia as a health career. As part of the American Medical Association’s “Doctors Back to School” program, the ASA members visit schools with primarily underrepresented middle school students. They have been providing early exposure to kids to raise awareness of what a career in medicine is about and the role that anesthesiologists play in patient care. Even during the pandemic, the physicians were able to continue the program, in the “virtual space” hosting the activity through Zoom. During these virtual meetings, the anesthesiologists highlight their journeys and challenges in pursuing anesthesia. Their ultimate message was that the path to becoming a physician anesthesiologist does require determination, but it is a rewarding profession. It doesn’t matter where you come from or even if you are the first one in your family to pursue medicine – you can become a doctor [10].

As more medical institutions are investing in today’s youth, it is important that their approach centers diversity, equity, and inclusion of underrepresented minorities in medicine. When patients can see their own identities reflected in their healthcare providers, it builds trust and rapport— pillars of a positive patient-provider relationship.

References

1. “Underrepresented Minority Definition | Office of Diversity and Outreach UCSF.” Homepage | Office of Diversity and Outreach UCSF, https://diversity.ucsf.edu/programs-resources/urm-definition. Accessed 25 July 2023.

2. Cregler, L L et al. “Careers in academic medicine and clinical practice for minorities: opportunities and barriers.” Journal of the Association for Academic Minority Physicians : the official publication of the Association for Academic Minority Physicians vol. 5,2 (1994): 68-73.

3. Patel, Shyam et al. “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Among Anesthesiology Trainees.” Women’s health reports (New Rochelle, N.Y.) vol. 3,1 414-419. 7 Apr. 2022, doi:10.1089/whr.2021.0123

4. Chiem, Jennifer et al. “Diversity of anesthesia workforce – why does it matter?.” Current opinion in anaesthesiology vol. 35,2 (2022): 208-214. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001113

5. Kana, Lulia A et al. “Experiential-Learning Opportunities Enhance Engagement in Pipeline Program: A Qualitative Study of the Doctors of Tomorrow Summer Internship Program.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 112,1 (2020): 15-23. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.11.006

6. “Inspiring Pipeline Program Continues to Score.” Inspiring Pipeline Program Continues to SCORE | UCSF Dept of Anesthesia, anesthesia.ucsf.edu/news/inspiring-pipeline-program-continues-score.

7. Office of Diversity in Medical Education. “Stanford Medical Youth Science Program.” Office of Diversity in Medical Education, med.stanford.edu/odme/high-school-students/smysp.html. Accessed 20 July 2023.

8. Winkleby, Marilyn A. “The Stanford Medical Youth Science Program: 18 Years of a Biomedical Program for Low-Income High School Students.” Academic Medicine, vol. 82, no. 2, Feb. 2007, pp. 139–145, doi:10.1097/acm.0b013e31802d8de6.

9. “ Changing the Face of Health.” FACES for the Future Coalition, facesforthefuture.org/about-us/introduction/.

10. Chang, Odmara L. Barreto, et al. “Reaching out during Challenging Times: The First Virtual Doctors Back To School ProgramTM Event.” ASA Monitor, 1 Aug. 2021, pubs.asahq.org/monitor/article/85/8/32/116108/Reaching-Out-During-Challenging-Times-The-First.

Credit for images: Marco Sanchez, UCSF Documents & Media