Written & Edited by Drs. Veronica Zoghbi, Carole Lin, & Victoria Fahrenbach

Global climate change has reached a tipping point in its effects on human health. The impact from human activity has hit many aspects of our daily lives and is now reaching catastrophic levels. While deadly heat waves, storms, floods, and wildfires are immediate effects occurring at an alarmingly increasing rate, numerous other consequences of environmental degradation are becoming evident, such as declining life spans, emerging infectious disease patterns, air pollution, and food shortages. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) state that climate change and extreme weather events have caused a disproportionate surge in natural disasters over the past 50 years.1 As healthcare providers, we should recognize that the healthcare sector is a significant contributor to global CO2 emissions. In 2013, the US healthcare sector contributed nearly 8% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions and it has been reported that If the US health sector were a country itself, it would rank 13th in the world for greenhouse gas emissions.2 We’ve all taken an oath to do no harm, and as anesthesia providers it’s now imperative we answer this call to order and make sustainability a priority in our daily practice. By making sustainable choices on the selection and performance of the anesthetic technique we can decrease our collective footprint on the environment.

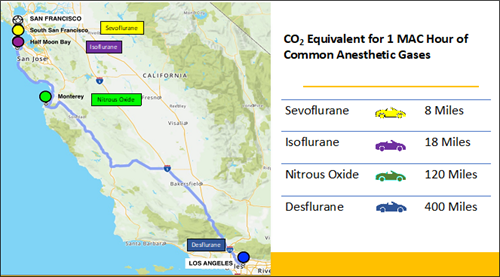

Anesthesiologists routinely use inhaled anesthetic gases to provide safe and effective anesthesia for patients undergoing surgery. For decades, we have ignored the contribution of volatile agents to global greenhouse gas emissions and worsening climate change. Inhaled volatile anesthetics undergo minimal in vivo metabolism and are exhaled essentially unchanged. In most institutions, anesthetic gases are vented directly into the atmosphere as medical waste gases. These gases remain in the lowest layer of the atmosphere for extended periods of time. Desflurane, the worst offender, persists in the troposphere for 14 years, while isoflurane and sevoflurane remain for 3.2 and 1.1 years respectively. Ryan et al. calculated the global warming potential of desflurane to be about 26 times higher than sevoflurane and 13 times higher than isoflurane.3 This study further estimated that in terms of global warming potential, 1 MAC hour of desflurane (at a fresh gas flow rate of 2 L/min) is equivalent to driving approximately 400 miles. In comparison, 1 MAC hour of Sevoflurane is equivalent to driving only 8 miles. As shown in Figure 1, these differences are drastic and highlight the devastating effects of Desflurane on the environment relative to Sevoflurane.4

Desflurane is clearly not a good option for the environment. Anesthesiologists continue to use this agent for its perceived ability to provide faster emergence and many may not be aware of its oversized contribution to the greenhouse effect and climate change. From 2001 to 2014, Desflurane emissions to the atmosphere rose from 150 to 960 tons annually as the global market for Desflurane increased 5.1% per year.5,6 Anesthesiologists should now reconsider whether the potential for faster operating room turnover and individual patient care outweighs the global health effects of this agent on the human population, especially when more sustainable anesthetics (Sevoflurane, Propofol, etc.) are readily available and provide equivalent clinical outcomes. Several institutions across California (some UC Hospitals including UC Davis and UCSF, Stanford University, Kaiser Permanente, Sutter Sacramento) have already removed Desflurane from their OR’s and continue to provide quality care for all their patients across all surgical settings. Providers at these sites are now using Sevoflurane or Propofol instead of Desflurane and are still able to maintain quick turnover times and manage high risk patients (bariatric, liver, kidney, etc.). In addition to minimizing their carbon footprint, these groups are also saving money by eliminating desflurane, as Sevoflurane is approximately half the price of Desflurane when using low fresh gas flows.

Knowing that volatile agents are escaping into the atmosphere continually,7 shouldn’t we select the most environmentally safe anesthetic technique? We can no longer ignore the impact of anesthesia beyond the patient and operating room. The individual choices of selecting the anesthetic gas, the induction technique, and adopting low flow delivery habits are simple but important steps that will help combat climate change without sacrificing clinical care. Even more critical is how we engage in larger policy action for changes to occur in the political and economic realm. Our choices can make the difference for our children’s future. We can all become AGENTS of CHANGE.

FIGURE 1. CO2 Equivalent for 1 MAC hour of common anesthetic gases 8

The global warming potential of each anesthetic gas was used to calculate CO2 emissions per hour (1 MAC hour using FGF of 2 L/min). With standard cars emitting an average of 350 g of CO2 per mile, the hourly CO2 equivalent for each agent is represented by miles driven. As displayed on the road trip map, 1 MAC hour of Desflurane is equivalent to driving from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

TAKE AWAY POINTS

- ANESTHESIOLOGISTS NEED TO BECOME AMBASSADORS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

- OUR ANETHETIC TECHNIQUE HAS AN IMPACT BEYOND INDIVIDUAL PATIENT CARE

- DESFLURANE IS ONE OF THE MOST ENVIRONMENTALLY DAMAGING AGENTS WE USE

- INDIVIDUAL PRACTICE CHANGES INCLUDE: ELIMINATING THE USE OF DESFLURANE, LOW FLOW MAINTENANCE OF VOLATILE ANESTHETICS (FGF

- SAFE AND QUALITY ANESTHESIA CARE CAN BE PROVIDED TO ALL PATIENTS WITHOUT USING DESFLURANE (INCLUDING BARIATRICS, LIVER PATIENTS, ETC.)

References

1. Climate and weather-related disasters surge five-fold over 50 years, but early warnings save lives – WMO report. UN News. Published September 1, 2021. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1098662

2. Pichler P-P, Jaccard IS, Weisz U, Weisz H. International comparison of health care carbon footprints. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14(6):064004. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab19e1

3. Ryan SM, Nielsen CJ. Global Warming Potential of Inhaled Anesthetics: Application to Clinical Use. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2010;111(1):92-98. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e058d7

4. Vollmer MK, Rhee TS, Rigby M, et al. Modern inhalation anesthetics: Potent greenhouse gases in the global atmosphere. Geophysical Research Letters. 2015;42(5):1606-1611. doi:10.1002/2014GL062785

5. Meyer MJ. Desflurane Should Des-appear: Global and Financial Rationale. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2020;131(4):1317-1322. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000005102

6. Saros GB, Doolke A, Anderson RE, Jakobsson JG. Desflurane vs. sevoflurane as the main inhaled anaesthetic for spontaneous breathing via a laryngeal mask for varicose vein day surgery: a prospective randomized study. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2006;50(5):549-552. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.001022.x

7. Committee AAH. Occupational disease among operating room personnel: A national study. Anesthesiology. 1974;41:321-340.

8. A long way to go minimizing the carbon footprint from anesthetic gases – ProQuest. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://www.proquest.com/openview/5d50aeb44536e0239a3508c80398a671/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=326357