- General Advice

- Longitudinal Prep Advice

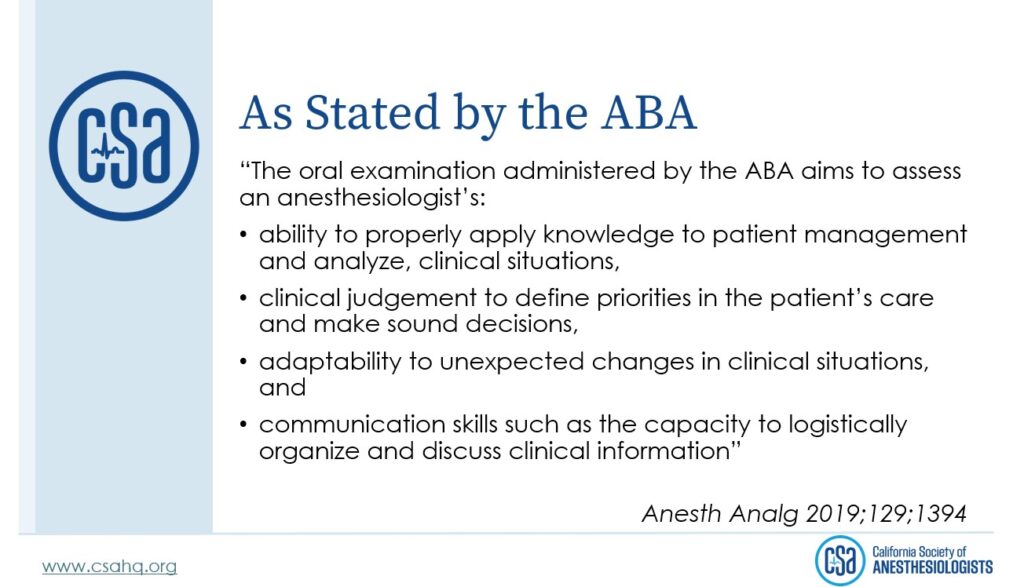

- What are the four key attributes of a consultant in anesthesiology?

- What references should I use to guide my study of topics in anesthesiology?

- When should I take my exam?

- How should I approach taking mock exams?

- Logistical Advice for Traveling to RaleighTips for the days (and the evening) right before the exam

- Exam Day Advice

- Advice from ABA Diplomates

- Join a study group, or find a 1:1 study partner

General Advice

The oral exam is not a test of facts, rather it is designed to assess who is capable of being a consultant in anesthesiology. Knowledge of facts (e.g. the vapor pressure of desflurane) is assumed since candidates have already passed the ABA’s written exam. Therefore, focus on showcasing your judgment and the rationale for your decisions. Be prepared to answer the questions “Why?” or “Why not?” Almost any answer you give will be followed by one of those two questions.

You already have vast knowledge and have successfully taken so many exams. The oral boards are about giving answers that you can back up by applying your knowledge and explaining those answers with confidence. There is no substitute for practicing aloud, and time spent practicing aloud needs to be set aside, distinct from the time you plan to spend reviewing content.

Access links to online resources and read CSA’s reviews of some excellent textbooks to use in preparation for the oral boards by clicking this link, and “look inside” some of these textbooks by clicking this link.

When answering questions, answer the question, then succinctly describe your rationale. Focus on the major problems, state the facts you are sure about, do not go into theorizing about scenarios you are not prepared to talk about, and do not make the patient sicker than they already are.

Longitudinal Prep Advice

At work, always think about why you are planning or doing a particular technique, and be able to justify those reasons. Establish back-up plans for any major decisions.

Find good resources that cover all the important aspects of anesthesiology. Use good textbooks.

For residents: Review the ABA content outline, identify your knowledge gaps, and prioritize your reading throughout residency to make sure you learn about those areas. Then review every subspecialty of anesthesiology in a current textbook (i.e. Miller, Barash), take copious notes to crystallize your understanding, and try making flash cards. After you pass the written boards, these resources will help you as you prepare for oral boards as well, although notes and textbooks alone will not prepare you for the oral board exam – you need to practice aloud to develop your presentation skills, which is an entirely different type of preparation from what any of us have done for all of our certifying exams up to this point in time.

Practice during all your cases, go through what possible complications could occur and how to manage them. Verbalize your plan out loud and when you can in front of a mirror.

Practice verbalizing your thought process when you work in the OR.

Make a study calendar (guided by your schedule, the ABA content outline, and perhaps the chapter list of the Yao and Artusio textbook). Work continuously on subjects over the period of time you’ve designated, checking your knowledge via frequent mock exams, taking time to explain the answers, asking for feedback when possible. Record yourself, have a relative or friend examine you, and ideally, find study partners.

Prepping well goes a long way towards doing well.

Anyone in academics has so many resources to draw on, and if you are in private practice, colleagues can help, and you can call upon mentors from residency and fellowship to give you mock exams as well. Most people are happy to give a mock exam or even a partial mock exam. Practice out loud talking to yourself or in from of a mirror. I didn’t record myself, but that is also a great way to practice.

Speak as if you were discussing care plans with an interested colleague or surgeon. Use proper terms and avoid slang, but don’t make speeches. If second attempt, focus on feedback from prior exam to guide study, and make sure to do mock oral with this program!

If you uncomfortable with public speaking, practice on your own, record yourself, and time yourself. Imagine you are discussing the case with a colleague you respect.

Make statements that you can defend, and explain them with confidence, succinctly, followed by an explanation of your rationale. Show how logically you deliberate about determining the differential, the diagnosis, and the right course of action. Show how clearly you communicate, and adapt to changing, uncertain or unexpected clinical circumstances.

Learn how to manage critical incidents, such as all of those described in the Stanford Emergency Manual, which is free for download. The manual lists quick steps that you need to have memorized, and if you can quickly deliver patient-oriented prioritized differential diagnoses and management algorithms for these seminal critical incidents, you will be on a stronger footing during your exam and you will not squander precious seconds pausing to collect your thoughts (and you will be equally poised to tackle these critical issues when seconds count in your practice). For a deeper discussion of the same critical incidents, as well as the key tenets underpinning crisis management in anesthesiology, an outstanding resource is Gaba’s “Crisis Management in Anesthesiology.” The shorter book “Faust’s Anesthesiology Review” is also excellent, for written and oral board prep, in addition to the more comprehensive key texts like Miller. Yao and Artusio’s “Problem-Oriented Patient Management” is also something I began using in CA1 year, all the way up to the week of my oral boards, to help orient my thinking toward the kind of issues that you need to focus on when you take oral boards. – Vanessa Henke

“After passing the written boards (ADVANCED exam), it’s clear that you possess the requisite knowledge, and by doing mock exams you’ll hone your ability to showcase (during your mock exams) that you possess the four key attributes of an ABA diplomate.”

— Vanessa Henke

What are the four key attributes of a consultant in anesthesiology?

What references should I use to guide my study of topics in anesthesiology?

The SOE covers the same content outline as the ADVANCED exam (written boards), and you can review the ABA content outline here. Learn how to manage critical incidents, such as all of those described in the Stanford Emergency Manual, which is free for download. The manual lists quick steps that you ought to have memorized, and if you can quickly deliver patient-oriented prioritized differential diagnoses and management algorithms for these seminal critical incidents, you will be on a strong footing during your exam. Importantly, once you are adept at swiftly, almost effortlessly describing how to manage critical incidents (because you’ve practiced aloud so much already for each critical incident, as well as for ACLS and PALS topics), you will not squander precious seconds during the exam pausing to collect your thoughts (and you will be equally poised to tackle these critical issues when seconds count in your clinical practice, and you’ll save lives because of the study you put in now).

For deeper discussion of the same critical incidents, as well as discussion of the key tenets underpinning crisis management in anesthesiology, an unparalleled resource is Gaba’s “Crisis Management in Anesthesiology.” The shorter book “Faust’s Anesthesiology Review” is also excellent, for written and oral board prep, in addition to the more comprehensive key texts like Miller that you are already doubtlessly using often. Yao and Artusio’s “Problem-Oriented Patient Management” is also something I began using in CA1 year, all the way up to the week of my oral boards, to help orient my thinking toward the kind of issues that you need to focus on when you take oral boards.

If you have time (or just for general reference) I also highly recommend Stoelting’s Anesthesia and Co-Existing Disease,” which consists of very concise chapters covering the co-morbidities that are most relevant in our practice of anesthesiology. Please refer to (1) longer CSA reviews of these texts, and (2) a short CSA PowerPoint featuring images of excerpts from these texts (and other recommended references) by clicking this link. – Vanessa Henke

When should I take my exam?

- Make sure that the exam week you pick works with your life situation.

- Schedule the exam whenever you think you will be the most prepared.

- Choose based on convenience: don’t choose based on budget, because in the long run the difference in what you spend on travel/vacation time will not make a difference in your success and well-being.

- Timing is a personal choice: “I wanted to get the most out of my fellowship and so chose to take the exam later (fall)” – compare this comment to another person’s advice: “Take the exam sooner rather than later, then study hard.”

- Note: there are more spring slots than fall slots for the APPLIED exam.

- There is also a nursing mother request window. See theaba.org and call the ABA if you might request special accommodations.

- Register as soon as possible after you get the notification that you can sign up, for the best selection. At first you sign up for your exam week, then later on you find out the precise day of your exam.

How should I approach taking mock exams?

- I would start 6 months prior to the exam. That usually give you an insight where you are, and how comfortable you are presenting. Once every couple of weeks until 2 months prior to the exam, where you can do mock orals once a week.I would at minimum do a mock oral at the beginning for some early feedback, another ~2 months before the exam, and another ~1 month before the exam.

- Take at least 2 mock orals in years 1 and 2 of residency, and several in the last half of the third year

- Take mock exams both early and late. If you know and have tough and intimidating people who will practice with you, try to do those a few weeks prior to the exam. It is helpful to start with more supportive practice sessions early (several months) so that you have time to study and practice and improve.

- Candidates should start prep as soon as they pass written exam, with mock orals beginning two months before exam date. Should stop prep a week before.

- I practiced consistently with a group of 3-5 individuals.

- Study groups are very useful. Also, it’s useful to have groups do mock orals as a group with a mock examiner so each member can learn from the performance of others, learn to relax in the situation, and benefit from hearing the critique of others.

- My husband was a surgeon and he helped me a lot. Also practiced mock exams with classmates taking the exam at the about the same time.

- I preferred working on my own, and having my senior colleagues do the mock oral boards with me.

Logistical Advice for Traveling to Raleigh

Schedule the logistics for your exam however you need, so that you will be the most focused for the exam.

Arrive at least 1 day early to adjust to time zone, get a great night’s sleep before, abstain from alcohol for a week prior to the exam, spend extra on a better hotel for food, comfort and sleep. Don’t study/cram for a day or two before the exam except if you have one or two areas of profound weakness – by then it’s really too late.

It is a very long trip from the West Coast. Plan an entire day to get there. If you can do an additional day early that can be helpful. The three-hour time difference is tough for getting to sleep at night and getting up in the morning, and your exam may begin early in the morning.

I had a hard time sleeping the night before (consider arriving early to allow yourself time to adjust to the time difference), and I had an early morning exam. Lots of coffee (but not too much!) in the morning helped, a long walk in the evening prior helped too.

Prioritize your physical and mental well-being leading up to the exam. Allow yourself to do things you enjoy and spend time with people who are important to you. The best way to feel comfortable doing so is to begin studying aloud early, but no matter what take care of yourself. Be kind to yourself.

Arrive as early as possible the day prior to exam. Lots of good food options adjacent to testing center. Make time for a beer after exam!

I used to live on the East Coast, so the time difference was less of an issue for me. Finding the lodging is easy in Raleigh.

Tips for the days (and the evening) right before the exam

- I imagine this varies by individual. I reviewed my notes, practiced a couple of stems, and reviewed the OSCE material.

- If you don’t know something by two or three days prior to the exam, you’re not going to know it in the exam room. Therefore relax, do yoga, meditate, go on a walk, and sleep. Don’t eat spicy or fatty food the night before.

- I arrived 2 days early and spent a day walking around and sightseeing. My husband came with me so it was nice. I stopped reading/practicing once. I arrived. I needed/wanted some time to decompress before the exam.

- I believe candidates should try to relax and enjoy the trip, not do prep/study immediately before the exam. Treasure this time as a right of passage as an anesthesiologist.

- Whatever you do, plan to not do anything exam related the day prior to the exam. Try as much as possible to rest your mind, and relax.

Exam Day Advice

- I reminded myself as I was at the test center that a candidate taking the exam probably walks in as a passing candidate (at least I think), that the test is theirs to fail, and I think this is reassuring advice. Also, I believe that the examiners are nice people with the best interests of the field and public safety in mind, although you should not expect them to provide verbal or non-verbal feedback during the exam. I liked to think that they were inwardly rooting for me, and I was there to show my best stuff. This made me feel more relaxed during my travel for the exam, and you are going to perform better if you are relaxed and allow yourself to shine!

- If you don’t know an answer to a question be honest so you can move on to the next question, and score maximum points.

- Focus and concentrate. Sit on the edge of your seat and actively engage with examiners.

- If you’re prone to headaches, take some Tylenol the morning of your exam. Caffeinate but don’t over caffeinate.

- Be calm, confident, and present yourself well.

Advice from ABA Diplomates

Tips from the ASA Resident Component

Here, the ASA suggests the 5 following oral board prep strategies:

- Split your study. The SOE and OSCE aren’t just testing your knowledge, they’re assessing how you convey what you know. It’s time to add materials that will help you organize and prioritize your thoughts, demonstrate your ability to communicate clearly, and apply knowledge to the real world. In addition, you’ll want to be up to speed on emerging knowledge and controversial issues facing the specialty.

- Read the questions carefully. Get in the habit of reading slowly and rereading, so you don’t miss any nuances or key considerations.

- Practice out loud. It’s not enough to know what you might say. Tap current or former ABA examiners and anesthesiology colleagues to gain experience answering questions spontaneously. Be sure to also record yourself practicing your answers and listen. Critique yourself—remove any “ums” and lengthy explanations so you can state your answers with clarity and confidence.

- Minimize travel stress. If you’re traveling for a live exam, reduce potential stressors by arriving a day or two early, carrying on your luggage, and knowing where you’ll need to be and when. Stay away from other examinees who are likely to share their stress with you. Eat and sleep well.

- Take a break before the exam. You’ve done the hard work. Continuing to study in the days just prior to the exam can undermine your confidence. Read some fiction. Watch a movie. Or go for a walk to burn off nervous energy.

Tips from CSA diplomates

Outlining: It’s key to develop a strategy that works for you, for outlining your thought process and work process during the critically important 10-minute period when you are alone with your stem, a pen and a sheet of paper, before you go in the exam room to greet your examiners and begin your 35-minute exam session with them. In this link, Dr. Louise Wen (a Stanford-trained anesthesiologist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center) describes in her succinct 7-minute youtube video (with over 16,000 views) her strategy for outlining. While there is no “right” way to outline, Dr. Wen’s comprehensive approach hits upon the highlights of what any outlining strategy needs to achieve. For more tips from the CSA about the outlining process, see our videos and written references on this topic (these videos have not yet been posted).

ABA Diplomates – Submit Your Advice

We continue to expand this section and would love to add your advice to support those preparing for oral boards. If you’re an ABA Diplomate and you would like to share your advice, please submit the form here.

Join a study group, or find a 1:1 study partner

The CSA is helping Californians find study groups and study partners. Connect with your colleagues on our What’s App chat here.